Experimental Reintroduction of Okanagan Sockeye into Skaha Lake

Supporting the Okanagan Nation Alliance’s and Canadian Okanagan Basin Technical Work Group’s reintroduction of sockeye salmon into Skaha Lake through the implementation of an adaptive management approach.

Location: |

Skaha Lake, British Columbia, Canada; N 50°08’59”, W 120°53’09” | |

Client: |

Okanagan Nation Alliance | |

Duration: |

1997 – Ongoing | |

Team Member(s): |

Clint Alexander, Darcy Pickard, and collaborator Kim Hyatt | |

Practice Area(s): |

Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences | |

Services Employed: |

Facilitation & Stakeholder Engagement, Ecological Modelling, Decision Support & Trade-off Evaluation |

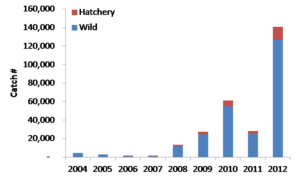

The reintroduction of Okanagan Sockeye to Skaha Lake has been a celebrated success, with the population dramatically rebounding in recent years to support harvest.

While the success of the sockeye’s recovery has been credited to many factors — including favourable ocean conditions and improved flow management within the Okanagan basin — the experimental reintroduction of sockeye into Skaha Lake has contributed to the rapid return of adult sockeye to their historic range in the Okanagan . The reintroduction program was led by the Okanagan Nation Alliance (ONA) in partnership with Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), the British Columbia Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations (BC-FLNRO), with funding originating from the Grant and Chelan County Public Utilities in the U.S.

Since the initiation of several restoration actions starting in the early 2000s, Okanagan sockeye have rebounded from their long-term decline with record-breaking numbers of adults returning to spawn in the fall of 2010. “Despite the effects of nine major hydroelectric dams on the Columbia River and channelization and flood control structure development in the Okanagan that reduced the length of the Okanagan River by 50%, they came back. While there are new pressures presented by ongoing climate change, it really shows the resilience of these fish in the best way,” says Clint Alexander, ESSA’s president and long-term project contributor.

Over a period of 17 years, our team helped support the scientific practices underpinning this adaptive management re-introduction experiment, beginning with facilitating its very first feasibility workshop in 1997. Our early work supporting the project’s adaptive management approach included establishing big questions, identifying uncertainties, exploring alternative hypotheses via life-cycle modelling and facilitating peer reviews of associated research and monitoring programs. Most recently, in 2014, we led an independent peer review of the reintroduction program’s 12-years in operation.

The Okanagan lakes and river system, once home to sockeye, chinook, coho and steelhead, had lost these fish.

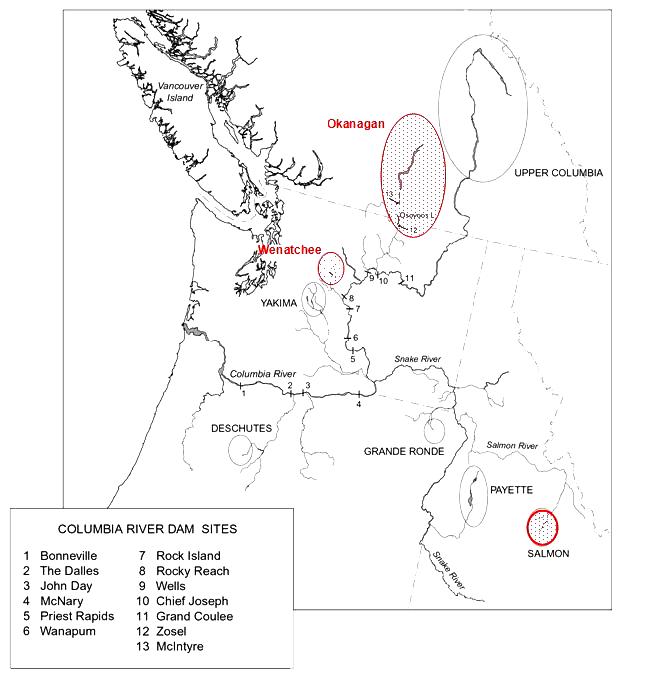

According to the traditional ecological knowledge of the Okanagan Nation and their relatives, sockeye salmon — in addition to several other salmon species —historically inhabited the waterways along Okanagan Valley from Okanagan Lake in the north down to Ososyoos Lake down by the Canada-US border.

Columbia River sockeye salmon populations. Red circles highlight subbasins with currently viable populations, grey-shaded subbasins refer to former sockeye populations for which habitat is no longer accessible. Source: Adapted from Fryer, 1995.

Due to the construction of nine dams downstream along the Columbia River and flood control infrastructure along the Okanagan Valley system the Okanagan sockeye suffered major declines as the passage of adult fish to nursery lakes and streams was blocked beginning in the 1950s. By 1994 fewer than 5,000 adults returned to spawn in the Okanagan River. Never before had there been so few sockeye returning to spawn.

The Okanagan Nation Alliance was highly motivated to restore this culturally significant fish and its associated harvest and cultural values they once enjoyed. Beginning in 1997 they began to explore what reintroduction would look like together with regional stakeholders, and scientists from the DFO and BC-FLNRO.

How to proceed with a reintroduction program in the face of unknown ecological consequences?

In 1997, the ONA hired ESSA to facilitate a workshop with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, The BC Ministry of Environment, the Colville Confederated Tribes (the Okanagan Nations tribal relatives in Washington State) to discuss the pros and cons of reintroducing Okanagan sockeye.

Initially the Province had concerns about the possibility of the reintroduced Sockeye competing with resident kokanee in Skaha and Okanagan Lake for resources. The Federal representatives with DFO also had concerns about the potential for disease transmission and food competition in the sockeye’s nursery lakes. Unfortunately, there was no credible way to address these uncertainties without conducting risk assessments and designing and conducting an experimental reintroduction program to generate sufficient data to evaluate the unknowns and effects. “Because of this, the parties eventually agreed to adopt an adaptive management mindset where the re-introduction program was designed as an adaptive management experiment that was reversible if significant negative effects were experienced by either natural Osoyoos Lake sockeye or resident Skaha Lake kokanee populations” notes Alexander.

“Early on, assisting three levels of government to come away from their entrenched positions and to clarify what actually mattered to them, as opposed to being opposed to something out of principle in the absence of evidence, was a pretty big contribution,” says Alexander.

Adopting an adaptive management program

The workshop we facilitated back in 1997 — together with early life-cycle modelling of the sockeye and peer review meetings we led at key junctures during the program’s first 12 years — helped the ONA and stakeholders realize and agree upon big questions, management objectives, key uncertainties and related priority monitoring efforts. “Couching everyone’s shared efforts within an adaptive management framework meant that it was okay to proceed without having all the answers before managers could take action,” explains Alexander. “At some point, you have to take a bit of a leap of faith if you are sincere in wanting to learn something.”

Following three years of risk assessment and project design, the ONA began in earnest a 12-year experiment to reintroduce sockeye into Skaha Lake under an adaptive management framework in 2004. Their work continues today, including construction and operation by ONA of a new salmon hatchery in Penticton.

Since then the Okanagan sockeye populations have rebounded, and the adaptive management program and related restoration efforts have been widely lauded as a cultural and ecological success. Resident kokanee stocks have not been compromised by recent stocking densities, and there have in some years been new harvest opportunities for multiple groups within and outside the Canadian Okanagan Basin.

“Given the recent and planned densities of kokanee and sockeye in Skaha Lake, room exists for Mysis shrimp, kokanee and sockeye to find a balance in the food web without triggering a winner takes all ecological story,” says Alexander. “While there are some trade-offs, the evidence doesn’t support the notion there can only be one or two fish in these lakes; responsibly managed, they have the capacity to support multiple species.”

As far as ESSA’s part in this success, over a 17-year period we provided expertise in adaptive management plan development, life-cycle modelling, statistical advice and impartial technical workshop facilitation where needed. We facilitated several multi-agency workshops and technical meetings to reach agreement on the big scientific questions related to the adaptive management plan that surrounded the reintroduction of these fish. We also helped develop the adaptive management plan in the reintroduction’s initial phases, helping the client group to identify key principles, uncertainties, hypotheses, and decision rules.

In the early 2000s we built a life cycle model for Okanagan sockeye that was used in various simulations to come up with the early initial safe target stocking densities for the sockeye. And lastly, we were called in twice to conduct independent multi-year reviews of the reintroduction project, once at the 4-year mark [Alexander and Pickard 2009] and most recently, the 12-year mark [ESSA 2015 report].

For the project’s 12-year review in 2014, we planned, facilitated and summarized outcomes of a peer review workshop on the reintroduction attended by 30 experts from Canada and the US.

This review identified a variety of new research and monitoring options and other adjustments to the experimental actions to more rigorously test remaining hypotheses regarding potential competition between the reintroduced sockeye, kokanee and other resident fish. Our recommendations also included articulation of the importance of clarifying decisions and decision rules instead of the path of endless questions.

“Despite long held beliefs by different stakeholders and levels of government, ultimately the only way to settle some of the residual disagreements over things like density-dependent interactions is to actually follow through on adaptive management actions related to the magnitude of contrasts and push the system around more than has been possible to date to see what happens,” concludes Alexander. “Otherwise you’ll just never know.”

Lessons from the Skaha Okanagan sockeye reintroduction program are now being used in part to guide potential future reintroduction and range expansion of sockeye into Okanagan Lake.